-

Posts

6,695 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

268

Everything posted by fuzzylogician

-

If it were me, unless there is a clear timeline that's short enough, I'd graduate and move on. Even with a clear timeline, things can often take longer than you expect when it comes to publications. Since you're certain that you want to get a job and move away, it doesn't make a lot of sense to stay for this potential publication, unless it's really at an advanced stage and you can see the end of the project (or at least, a point where a paper can be written up). It might be a shame, but once you're out of graduate school and have moved on, this won't matter anymore.

- 6 replies

-

- graduating

- breakthrough

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

If you have some other paper that could serve as a writing sample, you could consider using that, if the only reason you'd wait a year is to finish the thesis first. 1. It's probably easier if you have meetings with potential LOR writers before you graduate and discuss your graduate school plans with them. You might even do that now, to see if they think that my advice above about applying with a writing sample other than your thesis could work in your case. If you don't apply in the fall, you should also have meetings with all of your writers at the end of the school year, and use that opportunity to tell them about what you've done during this year, since your first grad school related meeting. Then ask explicitly about how to stay in touch and when to write them again about grad school applications. But since (I assume) you're graduating around May and applications are due around December of the same year, it's not like they're going to forget you, so there's not all that much you need to do. If you do stuff over the summer after you graduate, that would go in a summary email in the fall, around the same time as when you remind them that you're applying and they agreed to write LORs for you, and when you tell them which schools you're applying to, etc. 2. Again, there won't be that much you could or should do between when you graduate and when applications will be due. There won't be an LSA institute this summer (it's every other year, and it happened last summer). There are a bunch of others (ESSLLI, NASSLI, EGG, the summer school in St. Petersburg, the summer school in Cyprus, the one in the Himalayas) and they are a good opportunity to meet potential advisors at target schools and they are lots of fun, but it's also fine if you can't attend them. I don't really know of any post-bac positions other than the UMD one; you could look into being a lab manager somewhere (I don't know of any that are hiring, but you could cold-email some people to ask), or you might think of a one-year program somewhere if you need to strengthen your background in any subfield (there are some of those in Canada). Or, just get a job. A one year gap is not going to cause you any trouble down the line. 3. There's no point in submitting an incomplete application. No one will read your thesis months after the application is due. First off, it's not fair to other applicants, and second, the decisions will have been made by that time. Submit another sample, or don't submit at all. You didn't ask but I'll say this anyway: Stanford is a very different beast than the other three you mentioned as reach schools. You should think about what you want to get out of your grad school experience and try to focus a bit more.

-

Your ability to talk about the projects in detail, what you contributed to them, and what you learned from them, is usually more important than whether or not they resulted in a publication (and certainly more than whether that publication will be officially out by the time you submit your application). You might not be able to discuss all of your projects at length (nor should you necessarily want to), so I think it's wise to concentrate on one or two that are the most directly related to your interests and fit best with the schools you're applying to. (So you might pick different projects for different applications.) All of your projects should be on your CV under Research Experience, and you might want to choose LOR writers who can discuss all of your projects, if possible. Again, at this point in your career it's more about growth and potential than actual deliverables.

-

You’ll notice my reply was precisely to the post that suggested you edit the letter. And the forceful reactions you are seeing are in case anyone else reading this thread gets the wrong idea. This is a public forum, other people beside you might read your thread; and we want to make sure none of them take the advice of this other poster and commit a major offense like editing a LOR without permission from its author. That’s all. It’s not all just about your post or question, it’s about where the conversation went from there.

-

How do admissions committees evaluate PhD transfer students?

fuzzylogician replied to offthewall's question in Questions and Answers

The best way to leave a program is with their support. If the problem is with fit, as in there is no one to advise your research since it's evolved since you entered the program, ideally that's something that you can describe in your SOP and that at least one LOR writer can attest to. A corollary of this: it will be much better for your case if you have at least one LOR from your new program. Another corollary: it's good if you have good grades and some work to show for your time in your current program. You want to be able to tell a positive story about making the most of your time in your current program that leads up to something like "my program is not equipped to support these new directions that my research has taken, and therefore, with the support of my advisors, I have chosen to apply to Awesome U." (Awesome U is awesome and can support these interests, as I'll discuss at length.) If you just started your program a couple of weeks (a month?) ago, there's a good chance that adcoms might worry that you haven't given it program a fair shot. Or that you aren't actually focused, since you went through the entire application process last year and ended up in a program that couldn't support your interests. Either way, that presents a risk for a program that you might drop out again, hence wasting time and resources that could go to someone else who'll use them better. These aren't insurmountable problems, but they are potential red flags that you'll need to address through your SOP and LORs. -

You have "body 1", "body 2", "body 3", each making a separate point, supported by one or more arguments. These three points are separate from one another, but obviously related. I am asking, is it possible to make the main point of this shorter paper be just whatever is the main point of body 1/2/3, with all its supporting arguments making a strong case for this (now) one main point you're making, and with the other two points being condensed and hence at least somewhat secondary (= with some arguments either omitted or greatly reduced/sketched)? This is under the idea that it's better to do one thing well than three things half-assed. You can very well place this shorter paper in context by explicitly saying it's a reduced version of a longer paper where you spell out more completely arguments for the other two points that are now no longer the main one in the smaller paper. You can even make that longer paper available on your website for anyone who's curious to see the full paper. Caveat: I'm coming at this from my own field, which is not history, so take this advice as you will.

-

It's hard to answer specifically for such a general question, but in my experience condensing this much usually needs to involve some combination of rewriting/condensing sections and removing whole parts. In this particular case, I can imagine that one way to go is to condense the intro to about 4-5 pages; pick one of the main three arguments to be *the* main point of this shorter paper and spell it out in full (but with an eye for condensing where possible), a total of 8-10 pages; for the other two parts, give shorter versions of the arguments (my preference is to give strong detail for one argument, sketch others; but sometimes it's better to fully leave out an argument than do a half-assed job of explaining two, so pick wisely), about another 8-10 pages combined; then a shorter 1 page summary/conclusion (instead of the abrupt no-conclusion option, which I personally don't like as much. Iterate only what the main point was and why it matters, not how you got there).

-

Whoa. Do NOT modify another person's letter, you have NO right to do so. First off, you have a copy of the letter, but your recommender will submit copies directly when asked, the letters usually do not go through the student. So making changes to your copy likely won't help at all. Second, and more importantly, it's her letter with her signature on it. You should NEVER make changes to someone else's letter (or any other work, for that matter) without their consent. If it's really that important, you'll have no choice but to write her and let her know you've spotted a few typos.

-

I Give In-Thoughts on Chances?

fuzzylogician replied to GreenEyedTrombonist's topic in Anthropology Forum

Up front caveat: Coming at this from a different field. It sounds from your original post that you definitely have enough background and experience to be able to put together a strong application. Your GPA is great; your GRE is okay, but as long as it's above whatever threshold is required, I don't think it should cause you any trouble. I don't think that the fact that you don't have publications at this stage should be a problem -- you have some presentations under your belt and some plans for writing them up. As long as you can tell a coherent story about how these projects come together, what they've taught you, and how they inform you current/future plans, I think you're good. Others have covered the issue of fit, so I'm not going to repeat that. I'll make two points: the first is about the SOP; you want to make sure that you tell a cohesive story and that your past projects fit into the narrative. As an outsider, I had a hard time seeing the common thread in the projects you described above. I also think it's important not to dwell too much on who you were working for and more on what the project was about; what the outcomes were; if relevant, what actions were taken because of it; what your precise role was; and what you learned from it. It's better to go into detail and have a strong description of 1-2 projects plus a brief mention of other projects than have a brief list of 3-4 without much detail. The goal is to show that you can talk about the research coherently and that you understand it, and that you've learned and grown from doing it. I want to know how it informed your thinking and influenced your interests. I am somewhat less interested in the official source of funding or if a famous person was a collaborator, for example. Somewhat related, it sounds like you could have strong LORs stemming from these experiences, but I wasn't entirely sure if that is actually the case. You should get letters from people who can write precisely about those things I asked about above -- what was your role in the project? how did you contribute? what kind of team member were you? can you give good talks? come up with interesting ideas? collaborate? what kind of graduate student would you be? getting a letter from someone who taught you in a couple of classes is less effective than getting a letter from someone who supervised you on these projects you describe. On a related note, I also assume that one of these projects might contribute what will become your writing sample; that, too, is worth spending some time thinking about. If you're submitting something that's the result of joint work, you want to be *very* careful to make it clear what your contribution was, and also have a LOR writer discuss it explicitly to back up your claim of what precisely you contributed. A much safer choice is another paper/project, if one exists, that's the result of sole work. Either way, it's important to have a LOR writer address your contributions to any joint projects, else the adcom can't really know how to assess your own intellectual work and separate it from the group's. This, again, is why I stressed the importance of you giving details about the work you did in your SOP; it's one way for the adcom to at least see what you have taken from it and can articulate as part of your interests. -

This may vary by field, but I would personally not recommend book reviews as something students should do. Two main reasons: (a) as a reader, I don't really care what [random student I never heard of] thinks about [book]. I care what senior and influential scholars in the field think. So, it's not exactly an impactful statement to be making, nor something that's likely to get cited often, so therefore not necessarily a good use of one's time at this career stage. (b) Perhaps more importantly, going into a review unaware of political forces in the field could cause one to make some serious mistakes, in aligning oneself with certain forces without even being aware of it. You could be alienating parts of your field or suggesting that you are a certain type of scholar and not another, merely by having this not terribly important publication on your CV. I'd be very careful about potential implications, but mostly I just wouldn't do it, because as a junior scholar you might not even know what questions to ask.

-

Issue with word for organizing data - technical difficulty

fuzzylogician replied to Adelaide9216's topic in Research

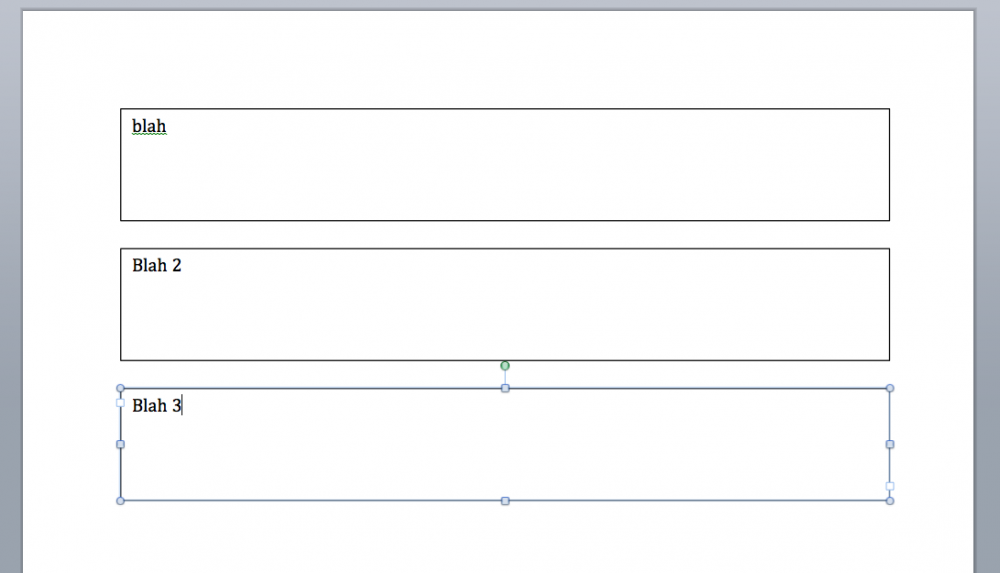

You mean something like the attached pic? Simplest way I know: Create a textbox. Format "line" to black. Reshape to the right width, copy-paste your paragraph into it. Copy-paste to create a new box, drag it so it's right under your previous box, copy-paste the next paragraph into there. Rinse, repeat. Not exactly high-tech, but does the job. Or, much better: Latex, use package mdframed. Or \fbox{} for short texts. -

Someone is messing with your head, and if he's a permanent fixture in your life, you need to find a way to remove him. Not only was it an unhelpful and mean thing to say, it also doesn't sound like it's rooted in any fact. You have a good GPA and some prior research experience. You have two projects that two separate professors consider publishable and will presumably praise in their LORs. That should allow you to write a strong and targeted SOP. You should have a strong writing sample based on one of these papers. You should have strong LORs, from all I gather. If you write a focused SOP and choose your schools wisely based on fit (+ get a decent GRE score), I don't see any reason why you shouldn't aim high and be successful. Cut the hurtful person out of your life and look forward with confidence. No guarantees or promises, but no reason to be overly negative, either.

-

Well, again. A self-aware version of #2 seems the most appropriate. #1 doesn't give much of any information at all. #3 has you already settled not only on the target disease but on the way to go trying to cure it, but you should probably be more cautious about making such detailed choices before you even start grad school. #2 gives the general intent and the kind of directions you think might be fruitful without getting overly specific in the wrong places, so therefore seems the most appropriate.

-

Please don't take this the wrong way, but is "non of the above" an option? Your options all sound incredibly naive and kind of obnoxious. A more self-aware version of #2 might be something like: "My long-term goal is to contribute to the effort to cure neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimers disease by expanding our understanding of how proteins function, through a close study of their structure and by probing their dynamics." As in, acknowledge that other (smart, talented) people have been working on this very difficult problem for a long time already, and be humble enough to show awareness of your own potential limitations -- you may not cure a disease all on your own, but contributing to the effort is something that a reasonable undergrad can aspire to.

-

Yeah, see, I don't know that I'd go this far. Ask your writers what they prefer; don't assume you know and decide for them. There's nothing stopping them from composing the letter completely independently of having the prompt. All they need is your documents (transcript, CV, SOP, whatever they asked for). They may or may not want the prompt in their inbox three months early. And they may very well prefer if you send them all in one go than one at a time plus an email telling them to expect the prompt.

-

Yes, though keep in mind: Some applications only send the prompts after you submit. Your professors may not plan to submit your letters this long in advance; while it's considerate of you to give them the extra time, take into account that the prompt might get lost in a sea of more recent emails in their inbox. So, check in with them closer to the application deadline to make sure that they still have the prompt, and offer to resend it if they need you to (most applications allow you to do that even after you submit).

-

Basics of Fellowships, Assistantships, Grants, and Stipends

fuzzylogician replied to samman1994's topic in The Bank

It depends on the fellowship. Obviously it would be premature to apply for dissertation-related funding before you're even admitted, have an advisor and/or topic. The NSF GRFP, on the other hand, does allow you to apply early, I believe. (As a non-citizen, I never worried about these details, but you might want to look them up.) The Canadian equivalents (SSRHC/NSERC) do, too. I would say it's important to make sure you're spending enough time on your applications first, but you might also want to talk to someone at your current department about whether there is anything you should be applying to this fall. -

Basics of Fellowships, Assistantships, Grants, and Stipends

fuzzylogician replied to samman1994's topic in The Bank

The answer to all of your questions is "it depends!". Some fellowships require a longer proposal (10-15 pages) which is essentially the same as a grant proposal, some require a much shorter proposal (my postdoc proposal was exactly 1 page long, including everything from project description to fit with the institution and sponsor). Some require you to show results directly tied to the project you proposed, some are more flexible. Some are specifically to support dissertation research, others are not. This is something to discuss with advisors, and is highly (sub)field dependent. It's always worth applying for prestigious grants and awards, even if you already have guaranteed funding from your department. It will make you more hirable and might give you extra independence. It might allow you to stay in your program for another year or two if you can arrange it, it might allow you to travel more; there are really not many downsides to having external money. -

Basics of Fellowships, Assistantships, Grants, and Stipends

fuzzylogician replied to samman1994's topic in The Bank

Two reasons: - If it's external funding, then showing that you have fundable ideas that you can articulate in a way that gets you money is very valuable, regardless of whether or not your institution would have fully funded you anyway. Sometimes you'll also get a higher stipend than you would from your institution, but not always. - Usually fellowships don't require the extra TA/RA work of assistantships, and that means more time to do research and less time spent on other things. That is usually conducive to doing more (and better) research. -

Unlike the resume, an academic CV can be as long as it needs to be. For a starting student, it may only be 1-2 pages, but it'll grow longer with time, and that's expected. There are plenty of threads you can find using the search function to help you with your question. One piece of advice is to simply look at what other students in your target programs are doing (which is more relevant than what professors are doing, since profs will have a lot more to write about than a beginning student would!). And the other is that you want to use the CV to highlight your accomplishments as best you can, given the purpose you're using it for. For grad school applications, you might have sections like education, awards (fellowships/scholarships/grants), talks, posters, papers, research experience, teaching experience, other (languages, programming skills, service -- depending on what you have and on the field). If you don't have anything to put under "papers", don't have that heading; if you have one poster and one talk, you might have a conjoined "presentations" or "papers and posters" heading, to make this part look "fatter", so to speak. For a while, you may not want/need to have separate headings for peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed presentations and publications, so you might just lump those under one heading. As long as you're not misrepresenting anything, you can make whatever choice looks best to you. As for extracurriculars and work experience, I wouldn't add those unless they are somehow relevant to your application. I'm sure there might be others who disagree with this advice. Same goes e.g. for putting specific (relevant!) courses you've taken, putting your UG GPA, or similar things on your CV. Opinions vary. For me, the main goal you should have in mind is helping your readers use the CV in a way that will maximize your chances of getting in. If your transcript does a good job of describing the classes you took, you're all good. No need to repeat that information in your CV (also, usually, no need to repeat your GPA unless it's very impressive; and even then, I'd remove it once you start your PhD). Don't generate extra unnecessary work for your readers; I assure you that they have enough other things to do, and they'll appreciate the conciseness. If, on the other hand, all the transcript says is that you took "LING 1234" and "LING 4321", I might not have any idea what you know, so it might not be a bad idea to add an extra page that very briefly spells out the actual names of those classes and what you learned (in 1-2 sentences!) -- e.g.: "LING 4321: Graduate Introduction to Syntax" or even an added like "introducing the foundations of modern syntactic theory within the minimalist framework" or some such, so your readers know what you actually learned in the class. This, of course, might be useful for grad school apps, but again would be something to remove later on. So for a lot of details, the answer to whether or not to include them is "it depends!".

-

If it were me, I would go with option (2) in the sense of finishing the MA at the current institution, assuming that your advisor will still support you through it. At that point, I would leave and either get a job, or apply for a PhD at another institution. Doing that should allow you to have a stronger profile applying to a PhD, with the support of your current institution, as opposed to if you dropped out and reapplied this year, though in your case it also shouldn't be terribly hard to explain why you're switching. But I do think this would save you a year that I don't see why you'd want to spend starting over at this point. If you do leave academia, this MA should be good enough, and if you go into another PhD program, you'll be in a strong position to do so, although depending on your field and target programs, you may end up having to repeat some coursework (which I personally don't see as a huge minus, but some people do, so there you have it.) I would also take this as a learning experience and look for a place with *at least* two, preferably three, potential advisors. People retire, move institutions, get sick, etc. more frequently than you might think, and you really don't want your entire future to be in the hands of just one person. Any future program you consider should really have more breadth and more ability to support you. In any event, I don't think that continuing without any support makes sense, so (3) is out; I think (1) wastes a year right now, where as later that time could be put to better use; and (4) is a little premature, since it doesn't sound like you can make that decision now. That leaves (2) as the winner.

- 1 reply

-

- retiring

- psychology

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Basics of Fellowships, Assistantships, Grants, and Stipends

fuzzylogician replied to samman1994's topic in The Bank

Getting hung up on wording isn't all that important, and there's also some variation in how these words are defined and used across schools and fields. Scholarships and fellowships are often (but definitely not always!) institution-internal funding sources for supporting students. They usually don't come with any strings attached in the form of service -- that is, you're not required to complete a certain project in exchange for the money. You have flexibility in the research you want to do. They can be merit-based or need-based. Graduate fellowships are not usually need-based, that's something that's a lot more common for undergraduates. Grants are also funds that are used to support student research, but they are often (a) institution-external (e.g. come from the NSF or NIH), and (b) are there to support a particular project with an already determined outline of predicted deliverables. Fellowships can sometimes (in some fields, very often) simply support the student regardless of the particular project they choose to work on. A stipend is what we call that part of the funding that actually goes to the student, as opposed to parts of the money that might go toward tuition/insurance/overhead... Assistantships are money you get for work, either an RAship or a TAship. When you TA, you are responsible for some combination of sitting in the lecture, giving office hours, grading, and leading one or more lab or discussion section. Responsibilities vary. RAships would usually entail doing work on a project for a professor, where they have money that's been earmarked for paying students to do work related to their (already approved) project. Their money might come from external grant or an institution-internal pot. It shouldn't really matter for you, with two exceptions: (a) some grant money is designated as for use only for US citizens or permanent residents, so if you're international you might not be able to get it; and (b) again if you're international, you aren't allowed to work more than 20 hours a week, so the official designation of the source of the money might matter so you don't exceed this requirement. Now, to make life even more confusing, sometimes the official designation of where the money comes from could be different from the actual work you're required to do. For example, in my PhD department, money from all funding sources was pooled into a large pot, and everyone was payed the same amount every semester. There was some amount of money whose source was fellowships and some whose source was earmarked for TAships, but where your money actually came from was independent of whether you happened to TA a certain semester or not. (Everyone had to TA some number of semesters, and you could choose which ones to do it in.) This had tax implications for some (international) students, but otherwise was basically invisible to the students. But as an international student I always made sure I would be on fellowship money*, because that would allow me to work for extra pay (as opposed to TAship money, which automatically assumes I'm working 20 hours a week and can't work any more), and for tax reasons that matters because of a treaty my country has with the US, where fellowship money got a larger exemption than TA money. * And so this is yet another reason why being good friends with your grad secretary is a good idea.. -

Concretely, two things: One: First year is often the hardest. It takes time to get used to juggling coursework and TAing along with research. The second semester is likely to be better, and second year will probably improve again because you'll likely have less coursework and you'll get better at managing your time. Have you tried talking to more advanced students about their experiences and how they handled the adjustment? Talk, specifically, to other international students who also had to handle adjusting to a new culture, climate, language, etc. This all takes time. It took me about a semester to start feeling acclimated into my PhD program and about a year before I actually understood what all was happening around me. I really started to enjoy myself some time in the second year, I would say. I can't promise that you'll be the same, but it might just be a matter of time for you, too, before you feel better adjusted and figure out how to make things work. At the very least, the few weeks you've been there couldn't possibly be enough to really have a sense of what your life might be like if you stay. Again, talking to more experienced students about how they make their situations work might help. Second: transferring is not usually that simple in grad school. More often than not, you'll essentially be reapplying and starting over from scratch. Many programs won't accept prior coursework, so you may have to redo that, too. That's something to look into. Also worth looking into -- is there a way to Master out of your current program? One way to leave without burning bridges is to get a Masters and reapply for a PhD at another school, stating fit as the reason you didn't stay in your current program. You'd be in a stronger position if you apply next year with one successful year under your belt and with letters from your current school, as opposed to this year, with just a few weeks into your program and presumably no support from your current school. It would, however, mean staying there longer (which I independently think you should do, by the way, as I stated above, to give it a real shot), so either way I think you need to start seeking help to learn to handle the stress. Less concretely, I've seen students get involved in unionizing; I am definitely not telling you not to, but the ones I've seen invested a whole lot of time into it, with not as many results, at least not for themselves and not immediately. If you do it, do it because you think it's the right thing to do in general, but it may not be the way to solve your own problems in the short run.

- 6 replies

-

- transferring

- phd

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

So, is it possible for you to discreetly look into switching advisors/topics? Advisors can have a huge influence on your life, and not getting along with them can be very hard. I personally think that having good compatibility with your advisor is a *lot* more important than the particular project you're working on (as long as you're not totally bored with it). I'd opt for the seemingly less interesting topic with the great advisor over the awesome topic with meh advisor any day of the week. So I think the question is whether there is someone in your program who you get along with who could be that advisor for you. Since it sounds like you had a good undergrad experience, hopefully you have some idea of what works for you, and now you also have some idea as to what doesn't. Maybe that means just meeting with people or showing up at their lab meetings to see how they interact with students. If that option could exist, it could be worth looking into. If not, another option is perhaps Mastering out of your current program and applying for another PhD program, hopefully this time with a lot more emphasis on finding an advisor that's a good fit for you. That would prolong your time to stability, but would keep options open and it might be a way to get yourself out of the bad place you're in now. Either way, I think you need to change something, because staying in an unhappy situation for years is just not healthy.